An Interview with Antwaun Sargent

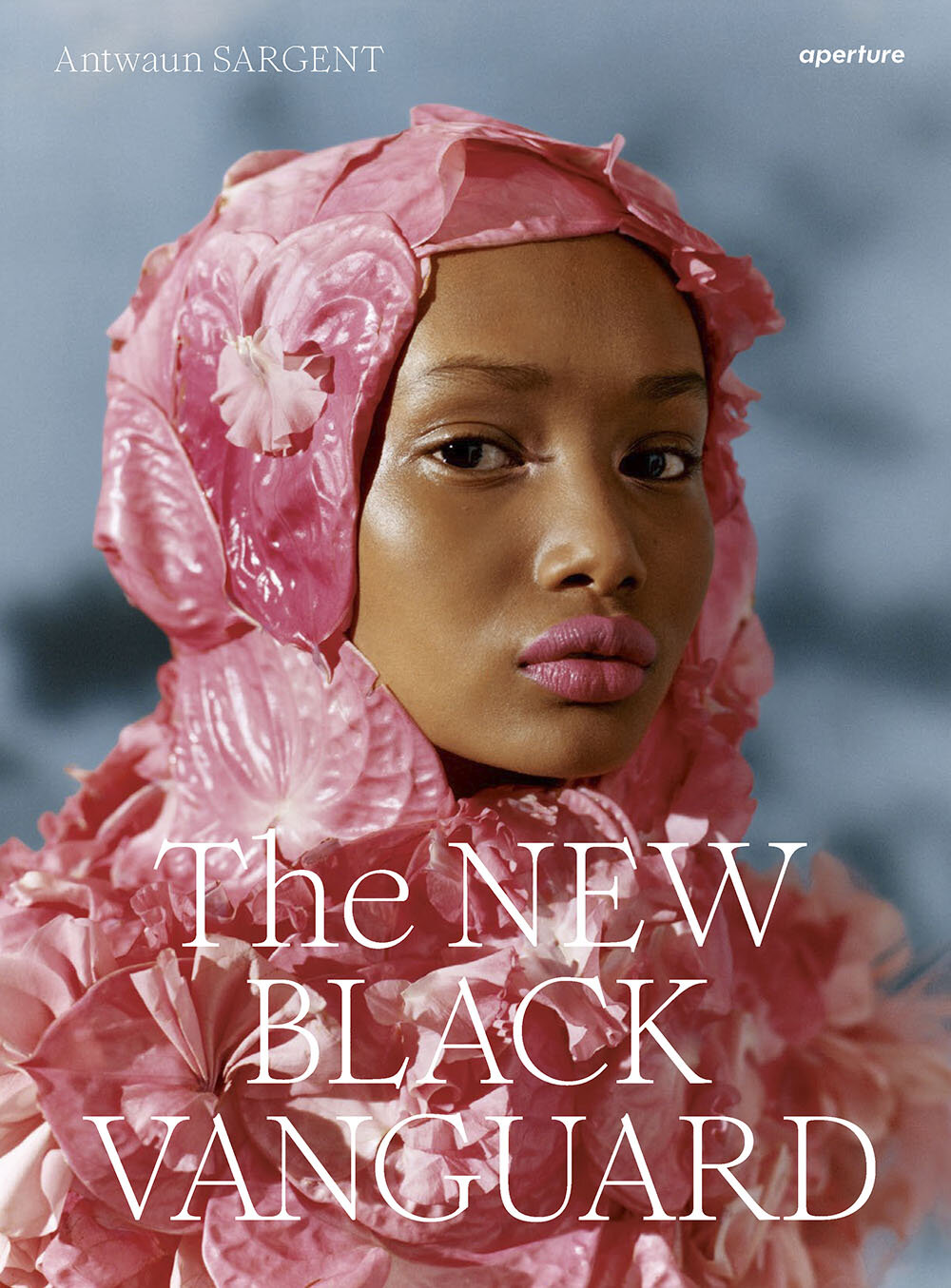

Antwaun Sargent is a writer and curator based in New York City. He began his career as an art critic in 2011 after graduating from Georgetown University, receiving a Masters degree in Education, and teaching for two years in Brooklyn. Now, Sargent is a constant presence in the art world—he has organized exhibitions for institutions like the Aperture Foundation and Jenkins Johnson Projects, written for publications including the New York Times and the New Yorker, and held talks everywhere from the Brooklyn Museum to Harvard University. In October 2019, he published his first book, titled The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion. Sargent talked to FORM about his book, his approach to working with artists, and the differences between writing and curating.

FORM: You’ve been committed to education for almost your whole career—from starting in NYC as a kindergarten teacher to educating the art world about contemporary black art. What do you want to teach people now?

Sargent: Education has been hugely important in my life. I think I’ve always had the desire to provide people with information that can be useful, that might challenge some of the stereotypes or notions surrounding beauty or communities or desires. Going from teaching to writing to curating, there is this thread that speaks to my interest in education.

I think for a time I was interested in writing about emerging artists who weren’t getting a lot of critical engagement. But right now, I think I'm more interested in the conversations that the shows or the writing produces. I’m less interested in a traditional curatorical or writer approach where I’m telling you what it is and what it ain’t. I want you to come in and see and have some sort of engagement and reaction.

F: All of your work is based on black artistic production and the celebration of black art. Do you think the art world has changed its perspective on black art? How so?

S: I have been doing this sort of work since I moved to New York in 2011. Back then—and this is 10 years ago, not to speak of what came before that—black artists didn’t enjoy this moment that they’re having now. There wasn’t this shift in concern by the larger art world to give black artists representation and space in museums and the things that their non-black peers enjoyed. That's what drove me to do the work that I was doing. I thought, I know all of these really amazing black artists, I'm friends with them, I'm in their studios, I'm around them—they have a lot to say, their work is good, and they should be having more critical engagement.

So I started writing and visiting the studios, just going and sitting with artists. It was mostly about getting their concerns out into the world. Whether you believed the concerns, or whether you liked the work—that was up to you. That’s where you have to join me in the critical heavy lifting. I'm putting onto the page what the artists are saying about their works—and then you get to disagree or agree, or come to your own conclusion.

Now, we’re moving into this moment where there are more resources and opportunities for young black artists and for black artists in general. Some have called this moment an overcorrection. Some have called it long overdue. It has changed the conditions in which black artists are not underrepresented—in some ways, they’re overrepresented in the conversation around contemporary art. I'm now interested in what that does to a generation that now has way more opportunities than previous generations. What does that do to the work? Does the work change? Do the concerns change? How do we come to understand what we call black art in a moment where there are more resources?

We're in this really interesting and heady time that puts a real emphasis on black painting and, specifically, on black figurative painting. You have artists who are now trying to play the market, artists who are deciding that they're going to paint. Generations before, people proclaimed painting dead, and the last thing an artist wanted to be was a painter—especially a figure painter. All of that stuff is a part of the conditions in which we curate shows, in which we write, and in which artists are creating work.

F: You’ve talked a lot about how black artists speak to their times. How has the way that black artists speak to their times changed in the past decade and how do you expect it to keep changing?

S: I don't know if there's been a change, because I think all artists just respond to the current social conditions. But I do think that there has been a widening of the concerns. We're getting a diversity of representations. And people are making work from their positionality in the world, which is wonderful.

People are seeing what else is possible beyond the Western aesthetics that have always been rewarded. There’s this moment of experimentation and really thinking about art-making within the space of communities and histories that have nothing to do with whiteness. Artists can reference whatever they want and not be penalized for not engaging the official canon. Artists like Simone Leigh, whose work is all about a conversation with black women and referencing that experience in her work. The aesthetic references come out of a process of black feminism and rituals developed by black women. Simone has been an artist for a long time, so that begs the question of why now? Why does the opening happen now?

We are in this moment where black artists are able to define more of their concerns and who they’re making work for. You have black artists—not collectors, not curators, not writers—making physical spaces for other black artists. Think about Theaster Gates’ Rebuild Foundation in Chicago, Kehinde Wiley’s Block Rock Senegal, Derrick Adams in Baltimore, Mickalene Thomas’ tête-à-tête. Artists are building their own institutions to support the work of other artists. This creates a less market-driven space where artists can be more experimental and raise the concerns that they want to raise.

F: Why did you choose fashion photography to be the focus of your recent book The New Black Vanguard?

S: It's about a liminal space in between art and fashion photography, the fact that the boundaries between the two have been obliterated by young black artists and photographers. Before, photographers worked in one or the other—you’re seeing that less and less. You have Carrie Mae Weems shooting the cover of W Magazine, you have Deanna Lawson shooting the cover of Garage Magazine, Mickalene Thomas for New York Times Magazine. And then you also have the younger generation, which I'm kind of concerned with in this book. Someone like Tyler Mitchell shoots a cover of Vogue, but also now has a show at ICP Museum. They’re less interested in these boundaries and are just making the work that they feel compelled to, but still drawing on histories of both.

The book was not some idea I dreamed up and then imposed upon works—this was what was happening in the world. It seems like a wholly unique contribution by young photographers of my generation, and I wanted to make sure we were having that conversation, I wanted to make sure that both worlds saw more clearly what was happening. And then I also wanted to make sure that I was nodding towards the rich history of black portraiture. I viewed it as an opportunity for us to see our images, an opportunity for us to understand our beauty, an opportunity for us to have our own museums, an opportunity to have our histories told in the space of photography.

Photographs by Tyler Mitchell, Micaiah Carter, and Stephen Tayo — three photographers featured in Sargent's book

F: In speaking about The New Black Vanguard, you said you wanted the book to be “anchored in the present, while looking at the past to imagine a future.” Why is it important for current artists to consider the past?

S: That was a choice that I made as the author, that was just one frame. I don't actually believe that artists have to always be looking to the past. I think they could be charging their own path. They could say: “Okay, I understand what that is. But I’m not doing that.” And I think in the book, you get some of that. You get a nod to history, but black photographers all over the world have different relationships to the history of photography, or don’t have a relationship to the history of photography at all.

I think of someone like Stephen Tayo—a Nigerian photographer who does what I call light-staged documentary photographs—and his desire to create comes from the fact that there are just no photographs of him as a kid. That was just not a part of the culture to have his picture taken like that. So his first project was to document the kids of Lagos. And that became documenting street style. I think that there are parallels to that in history, but they are not necessarily things that Stephen is drawing on. Being able to see those connections is great and it provides context, but it's only one perspective. The black artist does not have to be bound to history. We don’t go around asking white artists what part of history their works are connected to. There’s an assumed understanding that their work has connection to art history. I think that assumption should be made when we’re talking about black artists.

F: You’ve always emphasized the importance of artists’ voices to your writing about them. How do you balance your own voice with those of the artists you write about?

S: It’s something that I’ve gone back and forth on. When I was learning my way in the art world and in the writing world, I was a lot more interested in what they have to say. Now, my stance is that it’s important to take that into consideration, but if I invite an artist to be a part of a show, I’m open to it being a shared vision but it’s not their vision. I have to make sure my voice is there, because the artist doesn’t always see all the connections that can be drawn from their work. So I have to be there to hold a mirror up to their processes.

Artists operate in their own worlds, and sometimes they don’t see other artists creating alongside them, or how their work connects to other people. It’s a balance because some artists are very, very clear about how they want their work to be shown and seen, and other artists are a lot more flexible.

I remember having this conversation with Tyler Mitchell about his layout in the book, and he wanted his photos to all be the same size. And having this really robust conversation with him, I told him we can change the layout within some overall guidelines. And then he made a proposal, and we incorporated that. I think it’s a dialogue, a back and forth.

F: In addition to your writing, you’ve also curated several exhibitions. Does your approach to curating differ from your approach to writing? How and why?

S: The big thing is that with curating, you’re working with the artist. With writing, it’s about my relationship to the work. It is a similar process in the sense that with one, you're telling a story with words, and with the other, you're telling the story with objects. There’s a lot of crossover, but with writing there’s a greater freedom to draw connections and think about how other work influences or challenges the artist you’re writing about. With writing, there’s also a lot less worrying about if we can get the loan or if we can move the work halfway across the world. The limitations are different.

F: To me, all of your work also qualifies as activism. You’ve talked about “fighting photography with photography.” What would you say your work is fighting against, if anything?

S: Fighting photography with photography means that you’ve got to make images. If you’re an artist and you want to talk about the history of photography, you have to make images, you have to get into the arena. For me, my writing is a way to get into the arena and a way to challenge the fact that most major outlets only employ white art critics over 50, which skews the way we see art. I have a different experience, and I grew up under different conditions that provide a different perspective. My writing is my way of saying “here it is.”