A Make-Over in Modern Feminism

I hated make-up in middle school.

In the classic, self-conscious way of eighth-grade girls, my friends and I would pass scathing judgment on the girls in our class who dared to gloss their smiles or curl their lashes or pretend to be (as we saw it) anything mature and feminine. We tied up our hair, bought ChapStick with pride, and accused “those girls” of stealing our crushes with their curled hair and cakey foundation.

There was something despicable to me, even in those innocent years, about dressing up. There was a constant subtext in my mind that make-up was for girls who wanted boys to notice them — that stylish clothing was for girls who wanted to be women too soon. Maybe it came from some desire to stand apart from others, some desire to be taken seriously by the adults and boys around me; maybe it came from a surrounding world of gray-coated CEOs and the stony faces of the powerful women I wanted to emulate.

This is not a singular phenomenon: modern girlhood is a process of developing and re-evaluating one’s relationship with femininity. It begins with endless games of dress-up, with Barbie-pinks and fantastic displays of world-building and make-believe. It ends in the destruction of these tendencies in favor of what is respected, what is not sexualized, and what offers a woman a chance at individuality and equality.

The origins of the fight for gender equality lie in women fitting into masculine roles to access some semblance of fairness. Yet respect for the characteristically feminine is often cast aside in this process of attaining professional inclusivity.

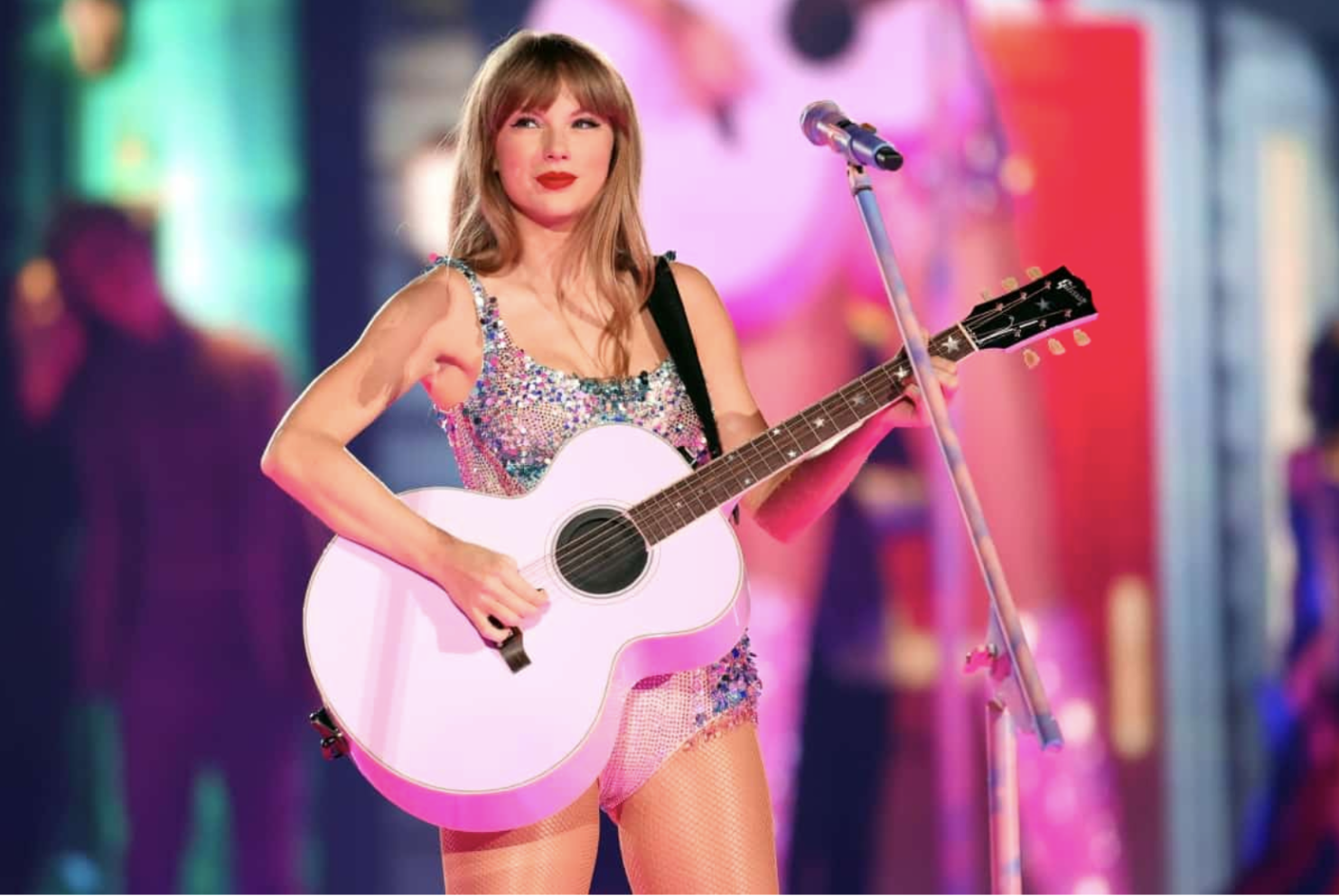

Then, this summer, droves of people dolled up in pink flocked to the premiere of Barbie, breaking box office records and making it this year’s global top-grossing film. Barbie, which also premiered mid-way through Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour, brought an unconventional perspective to our masculine formula for equality. Both Barbie and The Eras Tour have proved that there is immense popularity — and record-setting amounts of money — surrounding feminine traits and aesthetics that were previously pigeonholed into the disparaged world of girlhood. Glitter, costuming, make-up, perfect hair, and pink are all allowed (and respected and prioritized) in the Swift’s three hour show and in Greta Gerwig’s film.

Barbie is a masterpiece of cosmetic intricacies and thoughtful design. The set for Barbie Land uses a combination of 3D and 2D elements to create a whimsical representation of a young girl’s mind. This results in a landscape of artificial authenticity, in which paper backgrounds display a fake world with very real paint, and empty water glasses purposefully create the illusion of water, and fake houses form the nexus of a very plausible, very realistic Barbie world. Everything in these Barbie dream houses is actually 23% smaller than a human sized object, providing the effect that the actors are bigger than the items around them, and thus more doll-like than they really are.

The open, mid-century modern aesthetic of the Barbie dream house, the squashed walls of Weird Barbie’s house, and the pink sand at the beach all compound in a masterful design that makes Barbie Land look like the true product of childhood imagination (and a design that used up all of Rosco’s fluorescent pink paint in the process). Even Mattel, the Barbie headquarters, exists between the real world and the fantastical, with Ruth Handler’s ghost (the creator of Barbie) at home on one floor, and with a board of childlike men making business decisions on the next.

The costuming of Barbie also capitalizes on cinematic magic over anything conventional or realistic. The hair and make-up lead, Ivana Primorac, created individualized looks for each of the Barbies to ensure that everyone looked their absolute best. For Margot Robbie, Primorac hand-dyed wigs to uniquely match each of Barbie’s thirty costume changes. Barbie’s hair even changes — slowly losing extensions and volume — over the course of the movie, in response to her growing dejection over her experiences in Venice Beach. Ken’s appearance was also the product of countless hair-trials and tans, with special detail given to how he might match Barbie but not look too similar.

Some people might argue that this level of body make-up and purposeful set design is overkill for a movie about a doll. Maybe hundreds of trials to create those perfect wigs is excessive. Or maybe, it is part of the central point that the movie is making: that Barbie is a movie about the feminine experience, seeking to represent that experience in its entirety. That these details are a necessary method of glorifying the extraordinary pinks and the imaginative perfections of a conception of girlhood that is otherwise entirely disregarded by serious society. Maybe Barbie used thirty lip gloss colors to generate $1.28 billion dollars in the worldwide box office. Maybe Barbie demonstrated thematically and superficially that there is beauty in what others might brush off as both simple-minded and outlandish, childish and (proudly) feminine.

Taylor Swift created a similar crowd-wide effect with the costuming and design of her Eras Tour performances. She created a tribute to her ten albums with an impressive thirteen costume changes per show. She opens with a bedazzled bodysuit, then a Roberto Cavalli dress, then Etro dresses in different natural tones. Later outfits pay homage to her Reputation tour black bodysuits, her ball gown from the Speak Now tour, a flowy dress from Folklore’s 2021 Grammy performance, and a long shirt and faux-fur from her “Lavender Haze” music video. Every outfit has thematic purpose and responds to the aesthetic of a past album, an earlier story, a prior representation of herself and her discography.

There is a lot of pressure on female artists to produce not only music but also a persona surrounding their work that the public eye enjoys. Taylor Swift and many others have done this countless times, but in the Eras Tour, she takes inspiration from every step she took in her journey of publicity and unprecedented fame. In doing so, Swift validates every iteration of femininity she has represented. From the dreamy pinks of her Lover bodysuit to the edgy black of her Reputation era to the ethereal nature of her Folklore and Evermore dresses, she takes on a range of looks inspired by the girlhood notions of femininity. She embodies the pinks of Barbie-esque women and the sensual costumes of other eras and creates a production that grossed $2.2 billion in North American ticket sales alone.

Through sequined costumes and pink plastic heels, the music and film industries have explored money-making, serious presentations of oneself in new ways. The financial and public successes of Barbie and The Eras Tour reflect the talent of their creators as artists, but they also testify to a universal adoration of the sparkly aesthetics of their creators.

I grew up thinking that my life needed to unfold counter to the playful worlds of a traditional girlhood if I ever hoped to attain financial success and respect. However, perhaps success no longer needs to live so far away from these concepts — concepts like pop music, light color schemes, bright make-up, female friendships, and mother-daughter relationships. Ideas like creativity, gentleness, and feminism. The ability to walk on a stage, on a screen — in any combination of masculinity and femininity — and to be respected regardless. The ability to wear make-up, to wear ChapStick, and to not carry the baggage that we have been taught to wear with them.