APAHM: Asian American Artists

May has been Asian Pacific American Heritage Month in the United States since 1978. But this year, the month of celebration feels different. As the COVID-19 death toll surpasses 100,000 in the United States, the verbal and physical abuse of Asian Americans continues to intensify. In late March, the FBI warned that hate crimes against Asian Americans would increase due to the public’s association of COVID-19 with Asian American populations. Earlier this month, President Trump — who has repeatedly blamed China for the virus — responded to a Chinese American reporter’s question by telling her to “ask China.” Every day, Asian American medical workers are subjected to racial hostility while risking their health to fight the pandemic.

The surge in anti-Asian racism should not stifle our celebration of the Asian American community. Especially in the face of hate, Asian American stories and creations must be highlighted. FORM spoke with four Asian American artists about how their identities inform their work and aspirations.

Andrew Kung

Growing up in San Francisco, where being Asian American felt like the “norm,” Andrew Kung rarely reflected on his identity. In 2018, he went to the Mississippi Delta to photograph the local Chinese American community for the New York Times. There — in the swampy South, thousands of miles from the Bay Area — he came face to face with the difficulty and diversity of the Asian American experience.

“The first time that I really realized that Asian Americans have such varied experiences across the country was when I went to Mississippi,” Kung said. “I discovered how invisible Asian American populations are outside of major metropolitan areas.”

Kung’s trip to Mississippi prompted a deeper investigation of his own heritage and identity. He engaged in more conversations with his friends and parents about their experiences and delved into Asian American literature. The stories he found inspired his own body of work.

“How could my work make a statement about some of these more varied and nuanced Asian American experiences that people might not be aware of?” he asked.

Kung’s 2019 photobook, “The All-American,” features portraits of Asian American men. The series simultaneously celebrates Asian American masculinity and challenges its stereotypes. Since his book's publication, Kung has received many grateful messages from fellow Asian Americans who relate to his art.

“That’s when I knew I had the ability to uplift and bring visibility to my own community,” he said.

“The All-American” represents a spectrum of Asian American male experience. The men in Kung’s book — most of whom are his friends — are of different ethnicities and sexualities. He hopes his work educates the broader public on the wide-ranging experiences of Asian Americans and correct biases within the Asian American community itself.

“Educating our own community and bringing awareness to the intersection of gender, sexuality and race is a goal of my work,” he said. “That educational process within our own community is so important because it goes from inside-out.”

On all of his shoots, Kung staffs his team with Asian Americans. He also features the work of other Asian creatives: in “The All-American,” all of the models’ clothes came from Asian designers.

“I want to highlight the beauty in the clothes from these designers and how their Asian heritage influenced their craft,” he said. “I’m able to use that to further enhance the narrative of my work.”

Kung is currently preparing for a project inspired by 20th-century fashion photography. Like with “The All-American,” his new work aims to promote a complete Asian American image.

“I really want to showcase Asian American beauty. I want us to live in a world where Asian American beauty is normalized,” he said. “That’s not desexualized, not fetishized, but normalized.”

Susan Chen

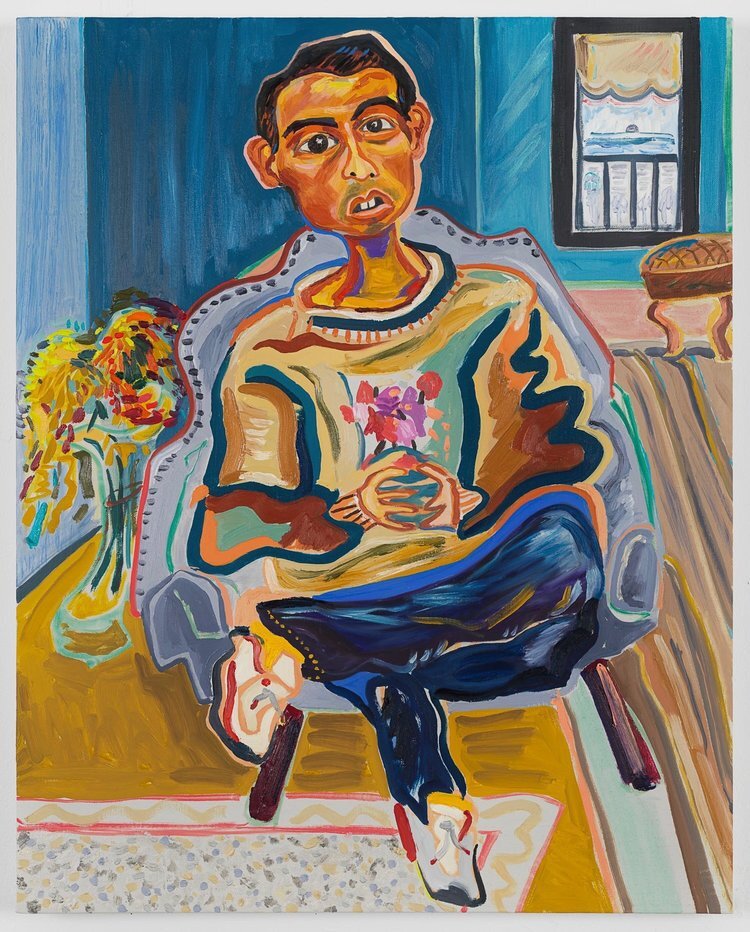

Susan Chen paints strangers she finds on the internet. These people are not professional models, so they fill the silence of five-hour studio sittings with conversation, turning the painting sessions into “therapy sessions.” Chen must multitask: listen and respond to her sitters’ musings while translating their likenesses onto canvas. This balance does not hinder her artistic process, but rather drives it. Her portraits are informed by her conversations with their subjects — she has no preconceived notions about these strangers, so her understanding of them comes entirely from their words and her painting.

“What I find most interesting about painting a sitter is trying to capture their truth.” Chen said. “I love asking people what their dreams are. It can be a dream as simple as wanting to have a garden one day. I think that’s my favorite part, wanting to understand someone’s desires.”

Chen wants her portraits — which are all of Asian people — to honor their subjects. But as much as she paints for other members of the Asian American community, her work also turns a lens toward herself.

“The thing with portraits is that there’s a real human being right there, and then it becomes almost like a mirror,” she said. “You’re painting someone else, but what you end up actually painting is yourself through them.”

Painting other Asian Americans has helped Chen navigate her own identity. From listening to the stories and problems of her sitters, she has become more aware of the collective Asian American experience and the challenges that it presents.

“I feel like I belong, but the outside world is telling me that I don’t belong.” She said. “But I’ve realized that it’s not me at all, it’s the whole population. It’s not even about us, it’s about how the outside world crafts us.”

Chen was born in Hong Kong and grew up between Hong Kong and the United Kingdom, so she is not Asian American by birth. She immigrated to the United States and completed her undergraduate studies at Brown University and is currently finishing her M.F.A. at Columbia University. Upon graduation, she will enter an art world that has been upended by COVID-19. Chen said that she paints in search for the meaning of “home” — she may not have found it yet, but she values the journey.

“I feel like New York City is this weird stopover. I’m stopping on the way to somewhere else, but I have no idea where that somewhere else is,” she said. “But I think painting is most interesting when you don't have the answers yet, and through painting, you continue to search for the truth."

Sirui Ma

In response to the hate crimes and anti-Asian rhetoric that have spread with COVID-19, Sirui Ma started the Artists for Asian American Federation initiative. The auction, which offers works by Asian creatives including Andrew Kung, will raise funds and awareness for the Asian American Federation, a nonprofit organization in New York City.

“Not only are we able to support this organization, we are also celebrating diasporic artists.” Ma said. “You don’t usually see Asian artists together in this way.”

Ma, a London-based photographer, is committed to representing people of color — especially Asian people — in her own work. She has shot campaigns featuring only Asian models for Gap, Stussy and other brands.

“There’s so much existing imagery of white people. Why do we need more? Growing up, I didn’t see a lot of Asian faces in advertising or media,” she said. “I find that to be a really central part of my work: how can I celebrate people of color without tokenizing them?”

The Gap campaign was especially important for Ma. When she was in primary school, her family could not afford the trendy Gap logo hoodies that her classmates were wearing. After being hired by Gap, she saw the opportunity to make the campaign personal.

“I saw myself in all of the people I photographed.” she said. “I thought that was a really powerful moment.”

In Ma’s photos for Gap, the models sit and stand together like family or close friends. But in reality, none of the models knew each other or Ma before the shoot. Ma always makes conversation with her models while shooting. She wants them to feel comfortable so that their connections look real.

“I’ve moved around a lot with both my parents, so I feel disconnected from my extended family. Also, my parents got divorced when I was around 18, so I’ve been longing to make my own family, whether that’s real or fictional,” she said. “I’m always seeking out relationships, and I want to create these believable relationships and partnerships in photographs.”

Ma was born in Beijing, but has spent most of her life between New York City and London. She moved back to London in 2017, but still feels that she “belongs the most” in New York. Her understanding of her identity reflects her kinship with the city’s community. Moving around has prevented Ma from feeling fully grounded, but she is grateful for the resulting perspective.

“Even though my passport is not American, Asian American is the identity that I connect the most with. It’s interesting to be stuck in that limbo of identity, where your passport says one thing and your heart says another,” she said. “It’s something I struggle with but also embrace. Without all these experiences of moving around, I wouldn’t have this unique viewpoint.”

Kim Anno

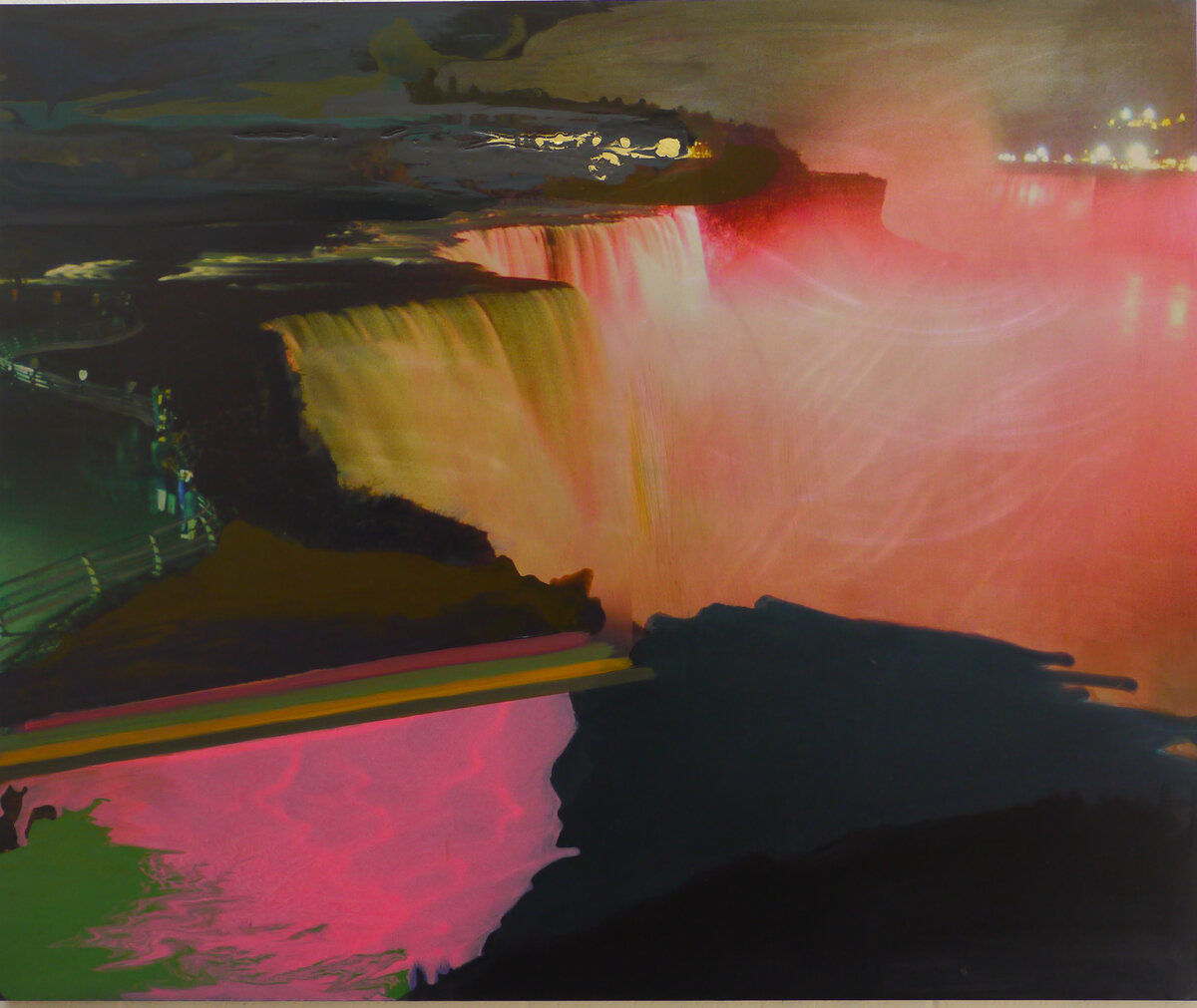

Kim Anno spent the first 25 years of her career establishing herself as an abstract painter. In 2009, she turned to making more socially conscious work after learning about the global climate crisis. Her work now confronts climate change and its repercussions, particularly rising sea levels.

“I grew up on the coast, and now our coasts are going to be different forever,” Anno said. “That means a lot in terms of equity. Those issues made me want to change everything.”

Anno, who is based in San Francisco, has had her work collected by the SFMOMA, Brooklyn Museum and other institutions around the world. She still paints, but her transition to more political art also spurred experimentation with different media.

“Being an artist, I like to stay alive and vital,” she said. “I think changing it up is healthy.”

Born to Japanese-Polish and Native American-Irish parents, Anno has to “choose what [her] identity is.” As she traverses between painting, film, photography and performance, she consistently draws from contemporary and ancient Asian art and culture. This past November, a trip to Japan helped her connect with her heritage and with the country’s cultural history. She completed a series of prints and paintings inspired by the Samurai tradition and made plans to collaborate with artists from Tokyo.

“My Japanese-American identity has definitely influenced my work, and will continue to,” she said.

Anno’s work addresses a host of issues, from coastal erosion to sexual identity. She is working on several projects, including two films: “Cuba,” which is about the country's LGBTQ community, and “90 Miles From Paradise,” which documents the rising water levels in Key West and Havana. She wants to bring attention to these issues without being didactic. She would rather her work raise questions and invite viewers to form their own conclusions.

“Art is a disruptor,” she said. “Art is about bringing out the nuances of issues in a way that makes people listen, especially those who don't expect it.”