MO Gallery: An Interview with Alex Wong

Alex Wong is the owner of MO Gallery, an art gallery in Shanghai. MO Gallery opened in 2019, and is currently hosting a three-part exhibition titled “Simply Stories.” Alex Wong talks to FORM about the making of “Simply Stories,” his career as a gallery owner, and his thoughts on the art scene in China.

Evelyn Shi: I came across MO Gallery’s “Tide Player” exhibition while researching ongoing art exhibitions in Shanghai, and I was immediately drawn by its theme and aesthetic style. Could you start by telling me about your current exhibition, “Tide Player”?

Alex Wong: So “Tide Player” is actually the first part of a three-part exhibition, “Simply Stories”. The second part is called “The Midnight”, and the third part is “Double Exposure”. Each part explores the greater theme, “Stories”, from three different angles.

About our overarching exhibition, someone wrote a book titled “Simply Stories”… I think it was Dong Qiao, a contemporary author from Hong Kong. Our exhibition name was inspired by the name of his book.

“Tide Player” is also the name of a book by Cha Jianying. The idea behind “Tide Player” is… well, the four artists we’re featuring in this exhibition are all modern Chinese artists born between 1982 and 1985. They witnessed the ups and downs of the birth of the Internet age, and they all graduated from art schools, so they’ve been educated in academic art. These factors really influence their work. They’re not like artists born during the 60s or 70s, whose work started maturing during the 90s and 00s when China’s development was just starting out. Today, China is changing every day, and these balancing and disruptive events will ultimately have an effect on our artists’ work.

“Tide Player” is a group exhibition, which means each artist will have a different interpretation of the theme. Each piece in the exhibition is a reflection of its artist’s creative process and an expression of their ideas and reality.

ES: Could you briefly introduce the four artists whose work is exhibited in “Tide Player”?

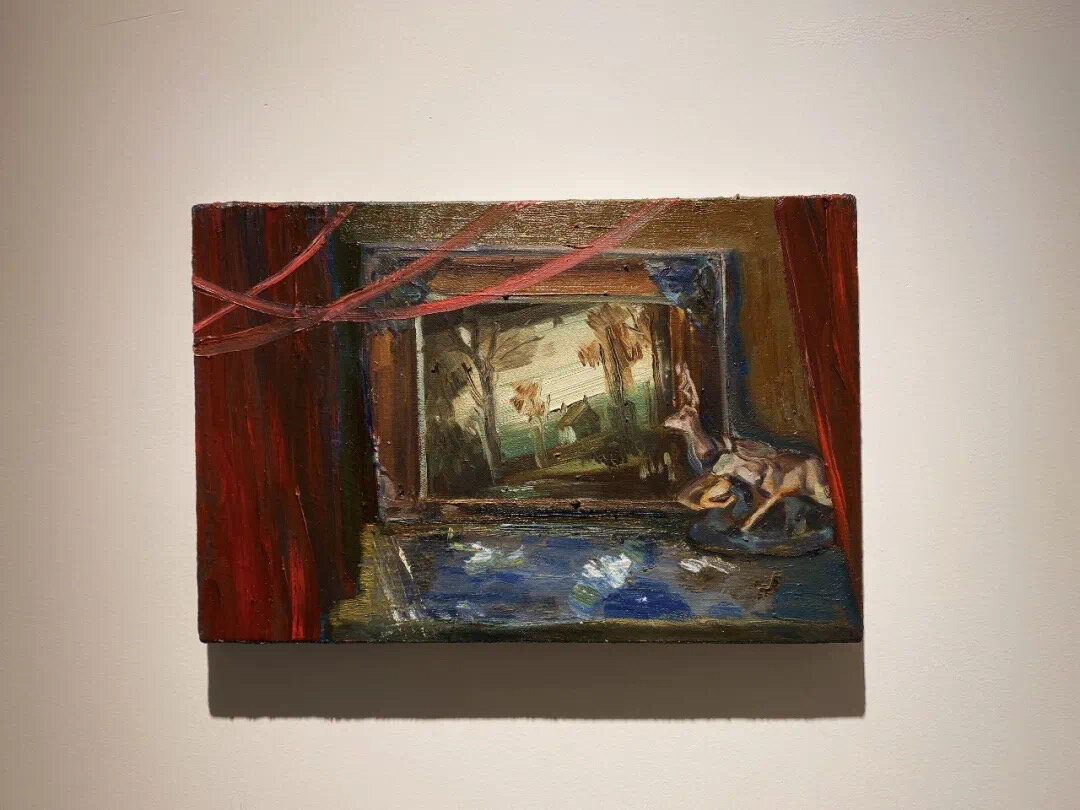

AW: Xu Dawei’s work is quite sensitive, with a focus on emotional projection. Xu Dawei is a listener, and he has a quiet, reserved personality. Rather than expressing outward passion, his work really reflects a quiet, reflective inner world. His work explores surreal thinking, feelings, and internal conversations.

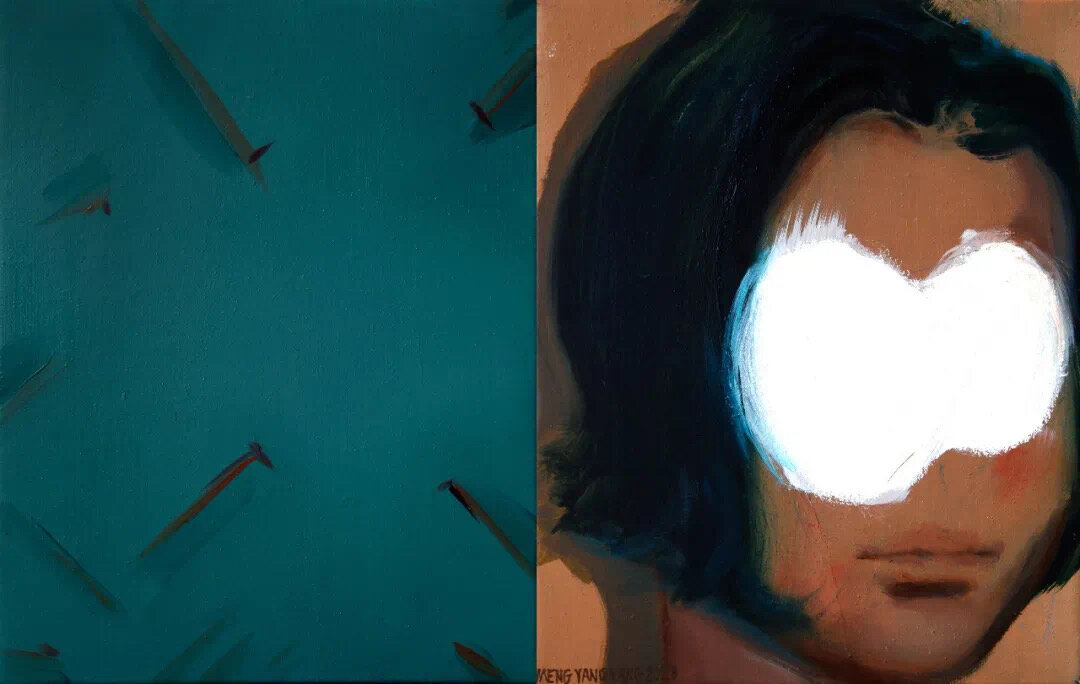

For Ge Yan, the second artist, art and personal growth are intertwined. Art is a projection of identity—his art is an externalization of inner thoughts and emotions. His creative process of bringing that inner world out is quite intuitive and even improvisational.

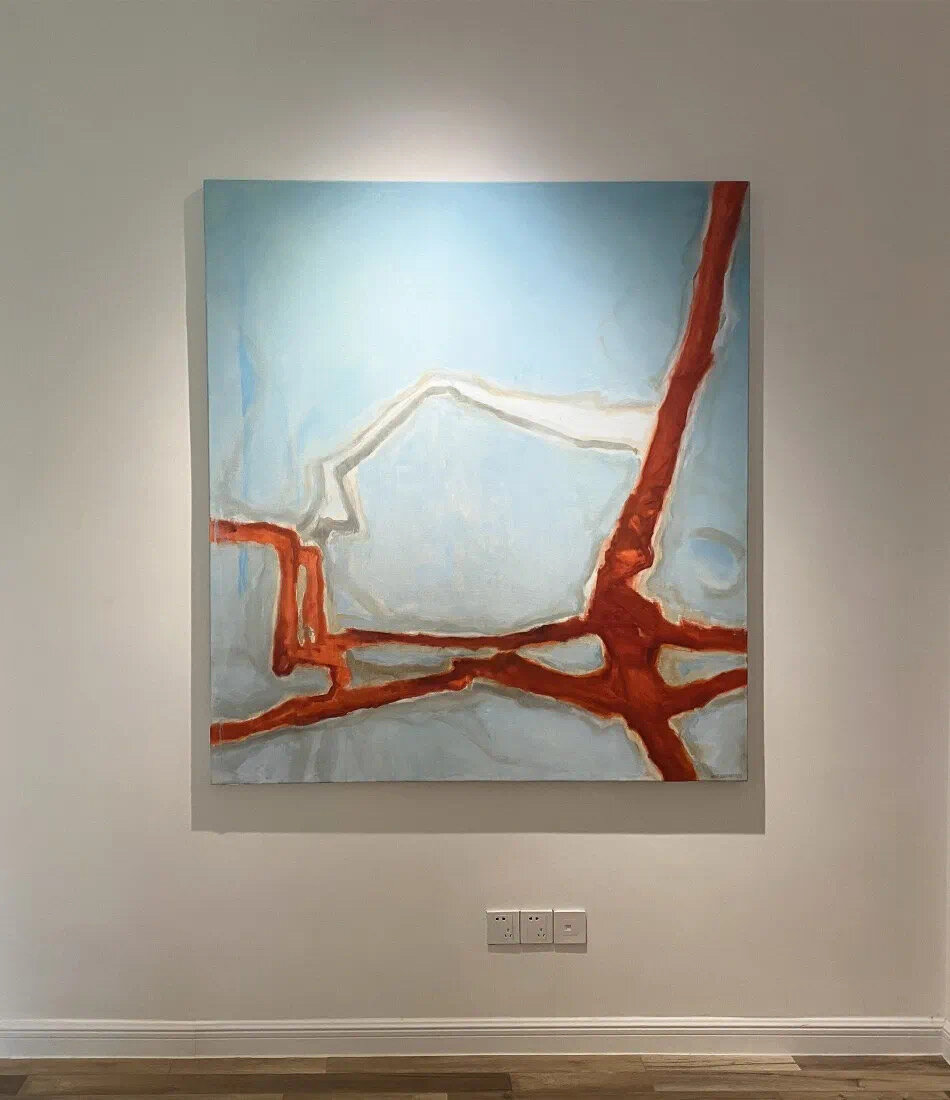

And then Meng Yangyang is from Sichuan province, so her work draws inspiration from northwest China’s geography, religion, and culture. If you compare her work with Ge Yan’s, her art is clearer and involves less storytelling. It’s very clean, abstract, and “hard”. I think her brushstrokes are what’s most attractive about her work—they are very free and flexible. In China, we have a habit of labeling art using stereotypical gender descriptors, which isn’t good. Artists are artists, they don’t need to be defined by gender. But if you had to, you could say Meng Yangyang’s work is very masculine.

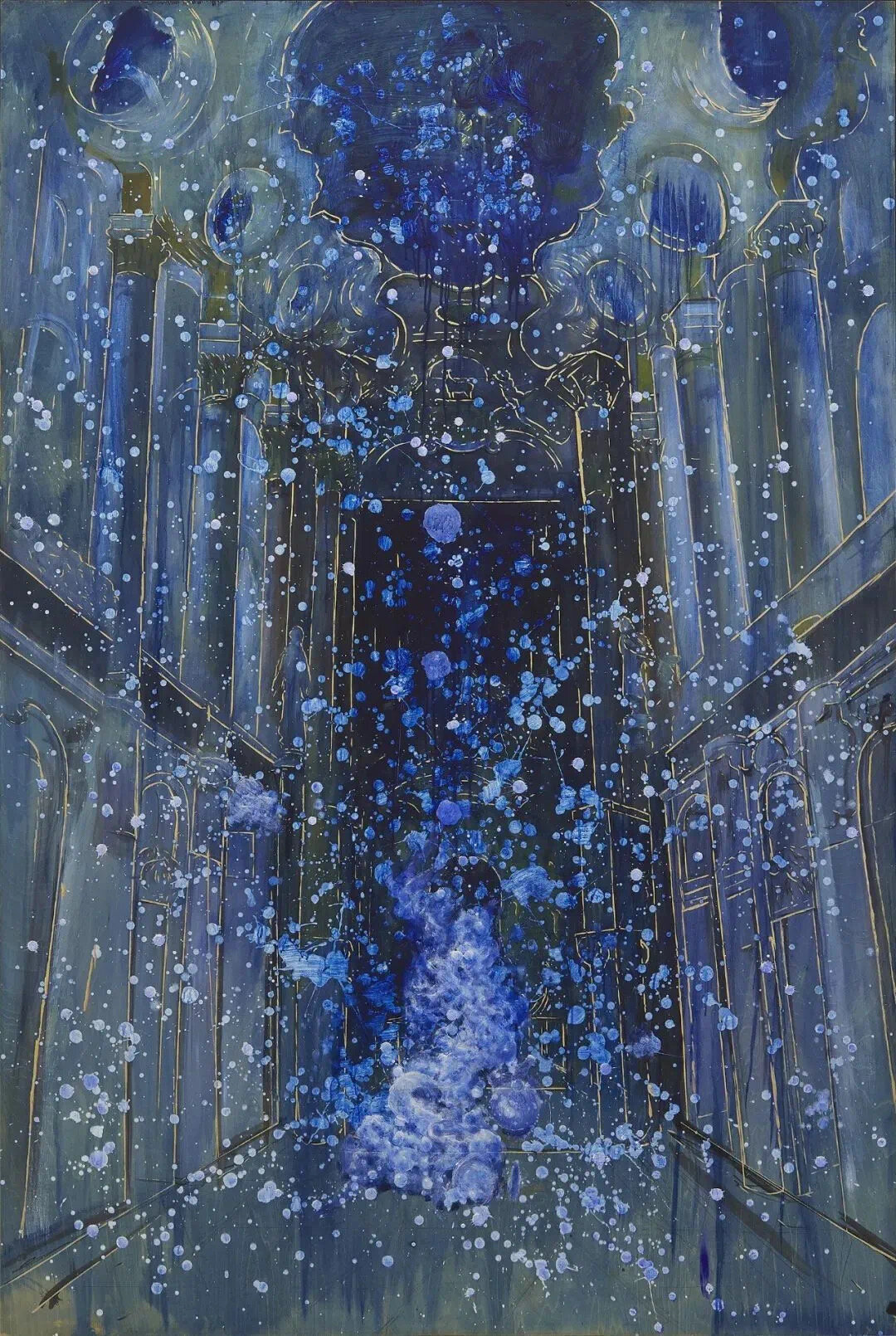

Xu Xinwu’s work is very detailed and intricate. He’s interested in issues about individuals vs. society, history, and bridging cultures, and he uses aesthetics and imagination to untangle the relationships between these things. His work isn’t about one moment—it’s about the combination of time and space, and every brushstroke is carefully thought out and placed with intent.

ES: How did you discover these artists? Can you explain the planning process for this exhibition?

AW: We’re an art gallery, so we maintain relationships with a lot of artists. These artists, too, are very involved in the market – they work with both Chinese and international art galleries, so we are very familiar with their work. The concept of “discovering artists” doesn’t really exist—we didn’t find these artists for the sake of this exhibition. Rather, we’ve observed their growth and development for a long time.

The four artists involved in “Tide Player” really exemplify the exhibition’s theme. Some of them have a more academic style, some are more detailed with a big emphasis on technical skill, and some have a very simple—even naïve—style. Not only does an artist’s style reflect events that have happened to them throughout their lives, it’s also influenced by whether their art is selling well, as well as trends in modern society. Anyway, all four artists have very unique styles—I can elaborate a bit on that later.

In terms of our timeline, each part of our exhibition will last about a month, with maybe a week in between to set up the next part. The first part, “Tide Player”, started in late September, the second part will exhibit in November, and the third part will exhibit in December, covering Christmas and the new year. I think the whole thing will wrap up in early January.

ES: How has the pandemic affected your plans for this exhibition?

AW: I think it doesn’t really have to do with the pandemic… I mean, art isn’t like a food struck selling steamed buns. Art isn’t dependent on traffic, and it’s not a short-term thing. Artists aren’t making art for a year or two, so the pandemic isn’t a huge problem.

ES: So you’re the owner of MO Gallery – tell me about your job.

AW: There are very different forms of art galleries. For me, MO Gallery is more of a family business. I’m not really targeting a mainstream audience—a lot of people will ask, “I don’t understand this piece, what does it mean?” I get these questions every day, but it’s hard to explain what a piece of art means. You have to consider what people in China understand art to be. I think that very little people in the mainstream have a deep understanding of art.

There’s honestly nothing too special about our gallery—I think galleries have always been a quiet affair. To me, my gallery is a place to express my inner world. I don’t know how to draw or paint, but a gallery owner must understand art. Let me talk a bit about the layout of the gallery, though. The first floor contains the exhibition, and the second floor is a whiskey lounge. On the third floor, we have a VIP room where we display our most unique pieces. Why did we make a lounge? I hope people can really connect with this place and get to know its employees and artists. We wanted to make the atmosphere more relaxed – a small space to host people who are interested in our art.

We don’t really have art curators here—in China, the word “curator” has a pretty strong connotation. Museums have curators, but an art gallery is a business. In China, curators tend to cater to a broader audience and the preferences of mainstream society. Art galleries, on the other hand, are more of a reflection of the owner’s personal aesthetic taste.

We’re always in constant communication with artists about what we like about their art and what we don’t—not just from a business perspective, but one that reflects a gallery owner’s personal taste. It’s the same for buyers—once they buy one, two, three pieces, they start to develop a taste, which we reflect to the artists. Art galleries act as a bridge between art collectors and artists. They are also a balancing mechanism between artists’ ideas and art collectors’ tastes.

ES: Could you talk a bit about your thoughts on the art scene in Shanghai?

AW: In my opinion, there aren’t many exhibits in Shanghai with true value. There are barely any proper art galleries or art museums in this city. Of course, there are a few good ones, but most are very average. Why? Most people interpret art as something trendy, and museums and galleries are moving in this direction. It’s not my place to judge if that’s right or wrong—there’s a market for it, so there must be a reason for it to exist. But I think a lot of galleries are displaying pieces with less artistic value—I guess you could call them decorations, rather than art.

China’s understanding of art is pretty different than from when I was in New York. I was talking to a friend in New York about Chinese artists, and I realized there is no phrase in English for “Chinese art.” When people think of “Chinese art”, they think of the ancient stuff they see in the China section of The Metropolitan Museum, but there’s a lack of understanding toward modern Chinese art. Does this mean modern Chinese art is a bunch of trash? Not necessarily—it’s just that people outside of China have a limited view of art from here.

Since modern art from China doesn’t receive much overseas recognition, it tends to gravitate toward styles that are broadly accepted by the Chinese public. 90% of Shanghai’s galleries and museums are just trying to appeal to trendy young people. You’re from China, you know the pop culture here—it’s like taking pictures in front of art galleries and posting them on WeChat. Art is treated like a quirky background for your Instagram photo. Many people’s appreciation of art ends at posting photos online for likes; there is little engagement with the art itself. I can’t say it’s good or bad—it’s just not my personal preference.

In the 90s and 2000s, modern art was just taking off in China. The art back then was very rebellious, pure, and creative, while a lot of art today lacks independence. Galleries are just focused on selling more entry tickets—the understanding of art itself is more immature.

ES: What you just said makes a lot of sense.

AW: Speaking of sense, I don’t think you can really make sense of art. You can’t really say why an artist decided to create their piece that way—it’s unnecessary and wastes a lot of time. If you just open your eyes and truly see the art – see its details, its description, the artist’s previous work – you’ll know what you’re looking at. You don’t really have to understand it. Say, you don’t really have to understand music. Sure, I like Jay Chow and you like classical music. If I like rap, why do I have to understand it? If you understand it, the value is kind of lost. Have you heard anyone say, “I’ve figured out Jay Chow?” Even if we interpret things differently, as long as we like the art, that’s all that matters.

Note: This interview was translated from Mandarin Chinese to English.