An Interview with Marcus Brutus

Marcus Brutus is a painter based in New York. A self-taught artist, he creates figurative paintings that tell stories of Black life. His work draws from everyday moments, as well as film, music, literature, and sport. Since his first exhibition with Harper’s in 2018, Brutus has presented his work in various solo exhibitions, group shows, and art fairs around the world. FORM spoke to Brutus about Black history, code-switching, and the motivations behind his work.

Dani Yan: In an interview with your gallerist Harper Levine, you talked about why you make the paintings you do. You said you wanted to make the Black figure central in images of humanity. Is the reasoning behind your paintings still the same?

Marcus Brutus: It’s similar, but I think now, I’ve changed the language to it. It’s a focus on the Black figure. I think using the word focus is a bit more inclusive. If you focus on something, it’s not that you’re only including that thing, it’s just the main idea of the work.

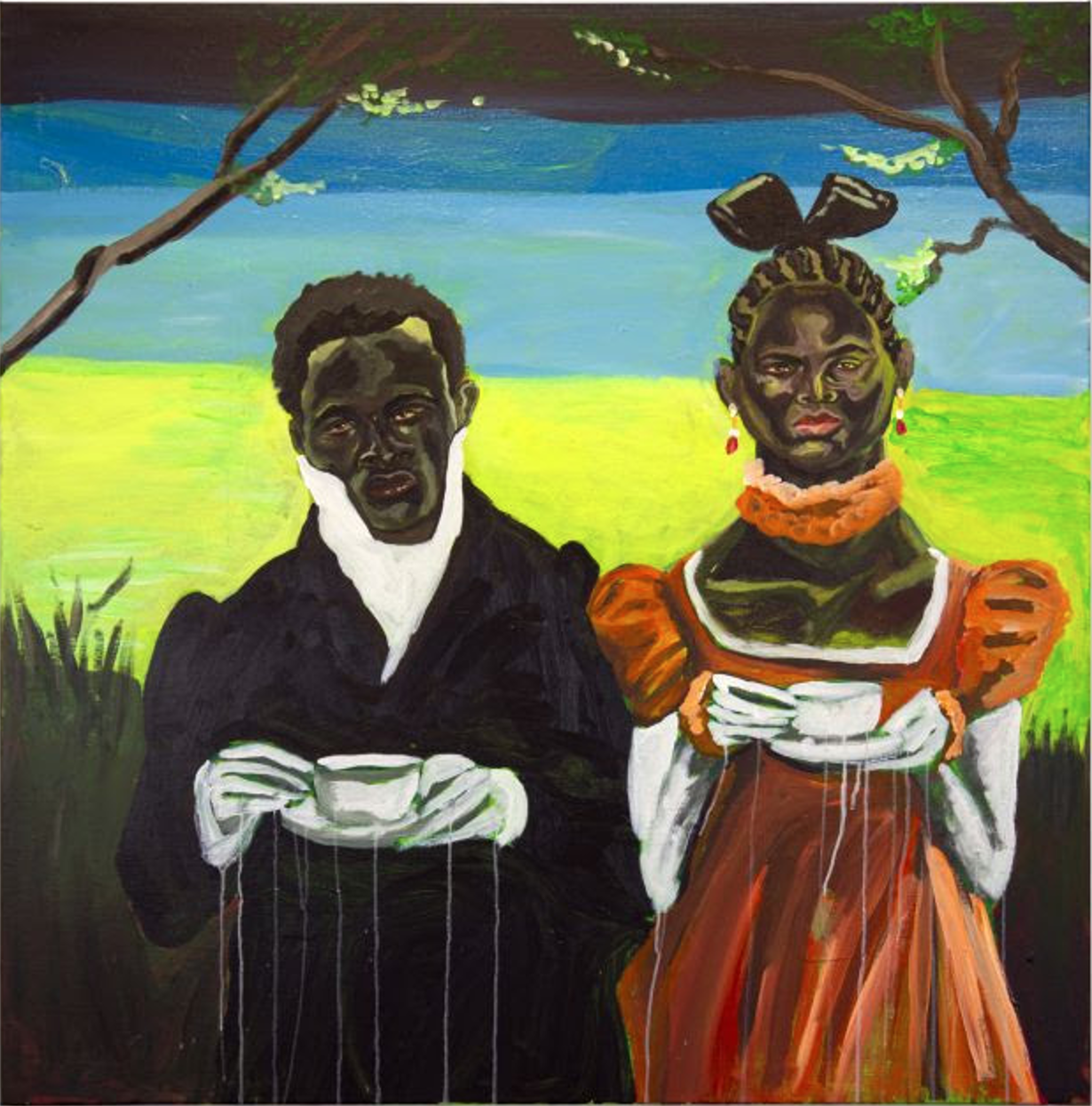

DY: In the same interview, you talked about becoming more comfortable with experimenting with your painting. Recently, I noticed more saturated and fluorescent cultures in your body of work “The Truth That Never Hurts.” How has your painting practice developed since your conversation with Harper?

MB: I want to incorporate elements of the process. So if there's a drip that happens when the brush is a bit too wet, I want to incorporate those little mistakes instead of trying to erase them to show the human touch on the work. It’s something that I’ve grown fond of.

The introduction of the fluorescent colors was to find elements that could make the painting pop. A lot of the subtext that I incorporate into the work are things that touch on traumatic experiences or traumatic histories, so these saturated or fluorescent colors can invite the viewer into the work. Then, you start to unveil that the work is dealing with more of a traumatic history. I don’t paint anything that looks dark on the surface. For me, the first goal of painting is to make something that looks good, that looks inviting. But if someone wants to engage with my work further, then I can reveal all the histories that are attached to it.

DY: With the fluorescent colors and abstractive elements that you talked about, I feel that your more recent work feels removed from specific times or settings. What time and space do you see your paintings occupying?

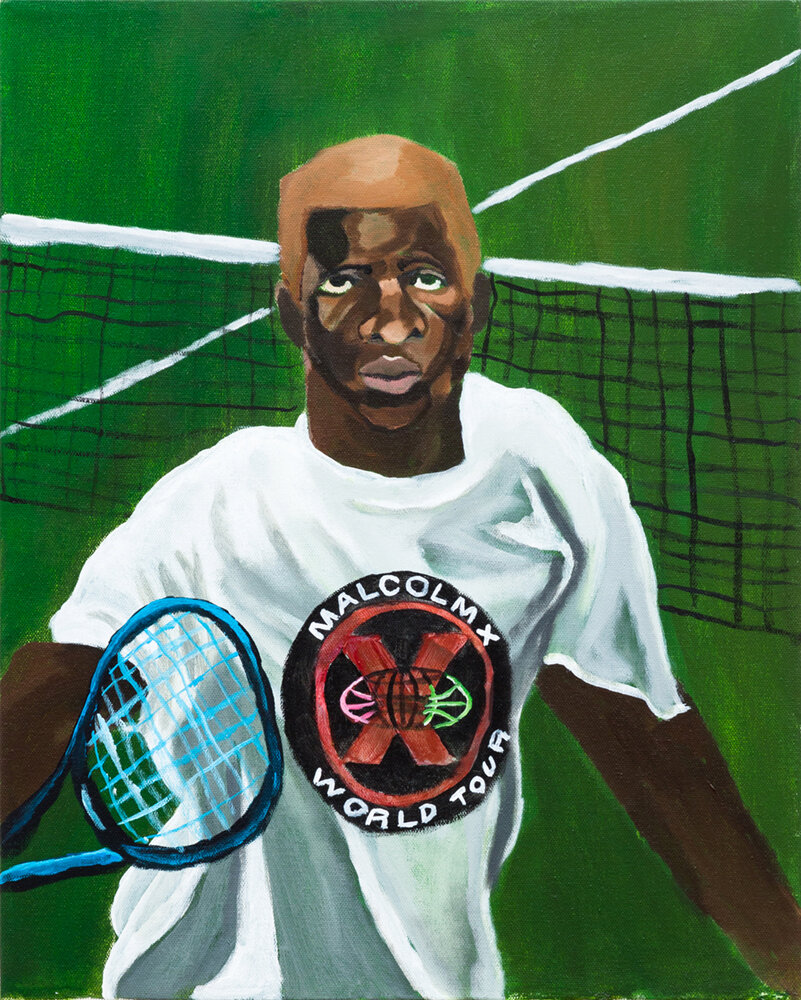

MB: Something I try to do is remove that element of time. For the most part, my work references the mid-20th century, but I like to go back and forth. Generally in life, I always form a link to things from the past when dealing with contemporary situations. I try to remove the sense of time in my work so I can reference something from the 1950s just as much as I can reference something that took place during the ‘90s. I decided to bounce back and forth to completely remove the sense of time in the work.

DY: I know you’ve learned from art of various forms, such as music by the Wu-Tang Clan. What do you want your work to teach your audiences? What stories do you want to tell?

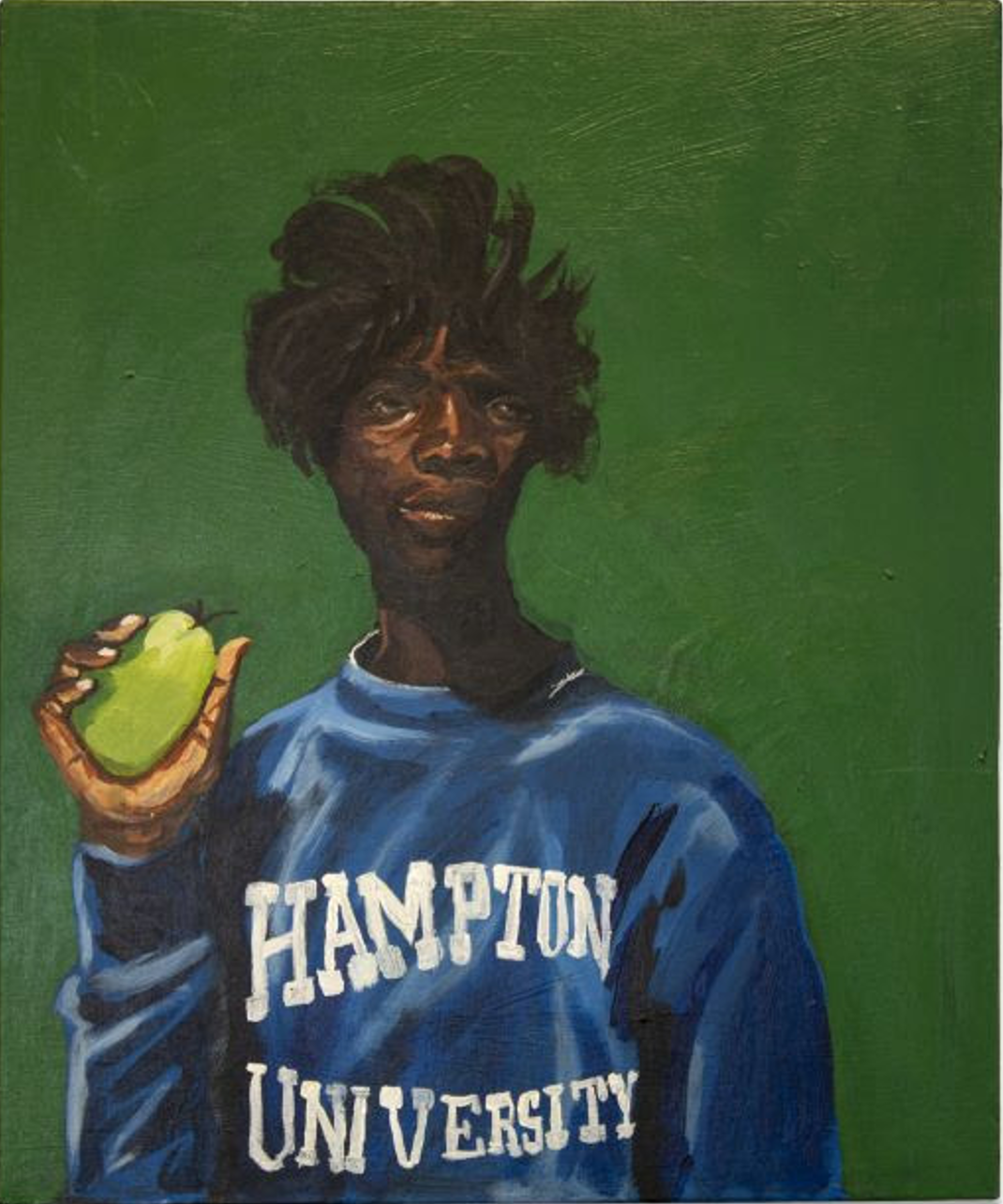

MB: I want to make something that can be for the unconventional learners, or something that tells stories that are a bit abstract. Under the umbrella of Black history, I’ve always been attracted to stories that are not readily available, that are not so relevant or pressing that they’re going to be a part of a curriculum. I want my work to exist in that sort of space — something that isn’t everyday. Maybe you wouldn’t have known about something if it wasn’t for my work.

Because I am a self-taught artist and I don’t hold any academic degrees dealing with history, those references were sometimes choices that came from insecurities. I felt that involving these intellectual histories would give me some sort of credibility.

DY: I definitely think those references add to your paintings, but I want to talk about some of the deeper ideas behind your work. One theme that really interested me was the division between personal expression and public presentation in your exhibition “Go to Work. Get Your Money and Come Home. You Don’t Live There.” Could you speak more about that division and how it manifests in your work?

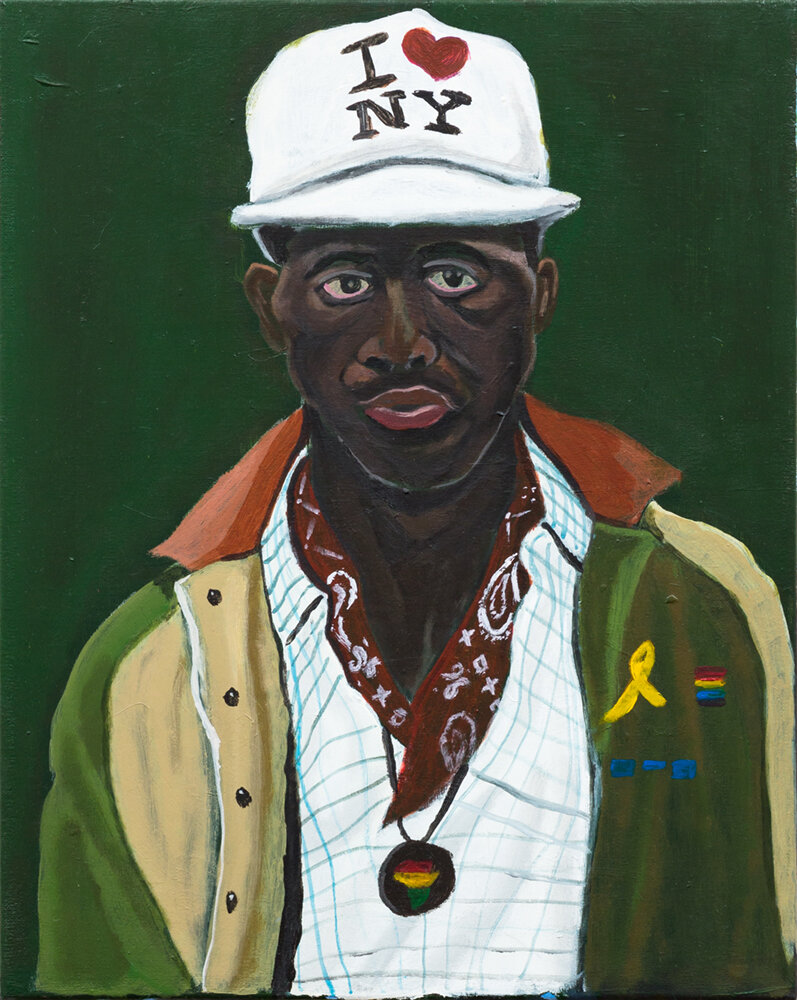

MB: There’s a sort of duality between how you present yourself in different spaces — for example, how you are in your workspace versus how you are around your family or your friends. The words you use, how you communicate, how you look. It’s code-switching, but not in a negative manner, but more as a skill or tool. There’s a flexibility where someone can be two versions of themselves — a skill gained from experience in a variety of settings.

DY: From that perspective, tell me more about the characters in your work. Considering people present themselves differently in different settings, what are the people in your paintings presenting?

MB: For the most part, unless I specify otherwise, the characters are imagined. They are supposed to depict an almost monolithic representation or reflection of Blackness. It’s never about the characters specifically. They’re supposed to represent an idea of a situation or an idea of a person.

I set out to create paintings that feel very ordinary. Because I feel like if you look at any group of people, whether they’re from a certain subculture or a minority or majority of the population, if you present them in a very ordinary fashion, there’s a sense of relatability. That’s what I set out to do because that’s what I see when I look at my life, when I look at my family. Even in the craziness of anything, there’s a sense of familiarity within a group of people. When you draw that, people find a sort of relatability to it. I wanted to present images that feel ordinary: someone jumping into a pool, someone walking around, someone posing. So it doesn’t matter what their cultural or ethnic background is, they’re relatable. I think doing that gives a very striking sense of humanity.

I stray away from individualizing or creating biographical works, because you can always find that one outlier. I want my audience to be able to look at a group of people and view their collective humanity.